Description

Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) is one of the most famous American journalists and writers, and winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the Nobel Prize in Literature. During the Spanish Civil War, he worked as a war correspondent and was a propagandist for the republican cause. He was one of the last chroniclers to abandon the field of the Battle of the Ebro. He left Barcelona and arrived in Tortosa on 4 April 1938 to report on the defence of the region of Baix Ebre from Franco’s advancing troops. He wrote, “At two o’clock this afternoon, Tortosa was almost demolished, evacuated of civilians and not a soldier in sight. Twenty-four kilometres away, they were fighting fiercely to protect Tortosa, the target of the fascists in their advance towards the sea.” His last report would be on 18 April 1938. He was close to Amposta, hiding behind an onion field next to the road to Tortosa. He wrote, “The Ebro Delta has a fine rich land, and, where the onions grow, tomorrow there will be a battle.”

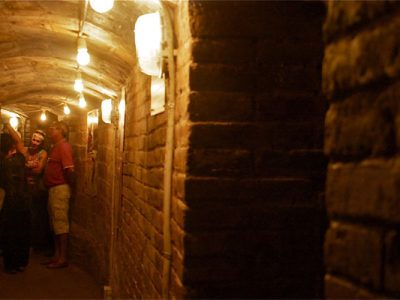

Shelter No. 4. We can start this route at the entrance to air-raid shelter number 4, where several companies offer guided tours. This is one of over 20 shelters built in Tortosa to protect the civil population from aerial bombings. Built under the slope of the Garrofer neighbourhood, air-raid shelter number 4 was paid for with public funds and was linked to another shelter at the end of Carrer Teodor Gonzàlez. It was the largest shelter in Tortosa, with a capacity for 400 people. It involves a system of galleries a metre wide and two metres high, dug into a ground of clay and rounded pebbles. It has a paved floor and brick and cement walls. A visit is highly recommended for those who want to get a feel for what it was like being in a shelter while bombs fell outside.

Plaça dels Banys. After a while we’ll reach Plaça dels Banys, one of the few remaining urban spaces in the old Pescadors neighbourhood (fishermen’s quarter) in Tortosa, which was completely destroyed by the Italian air force. The history of the Pescadors neighbourhood dates back to the city’s origins as a port and trading hub. The three-engined Savoia-Marchetti S-79 and S-81 of the Aviazione Legionaria delle Baleari, together with the German Heinkel He-59 hydroplanes of the Condor Legion, were the aircraft used to attack Tortosa. The main targets of the air raids were the bridges, the railway station, the power station and the workshops producing war materials, located mainly in Ferreries. The worst-affected areas were the neighbourhoods of Pescadors and Ferreries, and the area around the station and bridges. Between 23 February 1937 and 30 December 1938, Tortosa was the target of 77 air raids that caused 92 deaths and dozens of injuries. The most destructive attack took place on Good Friday, on 15 April 1938, when the city was hit by 12 air raids in which 54 tons of bombs were dropped.

Ernest Hemingway’s article “The Bombing of Tortosa” has become one of the most iconic texts of his coverage of the Spanish Civil War: “Above us in the high cloudless sky, fleet after fleet of bombers roared over Tortosa. When they dropped the sudden thunder of their loads, the little city on the Ebro disappeared under a mounting yellow cloud of dust. The dust never settled, as more bombers came, and, finally, it hung like a yellow fog all down the Ebro valley.” That evening, Hemingway made a terrifying reflection: “There were many reasons impelling us to leave Tortosa and go towards Barcelona, these include life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

Plaça de la República. Our next stop is Plaça d’Alfons XII, which, like other streets and squares, changed its name during the Second Republic when it was known as Plaça de la República. It is located right in the heart of Tortosa and is surrounded by majestic houses. During the air raids, many Tortosins took refuge in the suburbs, outskirts or in country houses in the mountains.

Municipal market. The municipal market was also damaged in the air raids and, during the reconstruction, some of the decorative elements of the façade were lost. The market symbolised the problems of replenishing the city. In November 1936, around two thousand refugees arrived from Pozoblanco (Cordoba), Toledo and other areas surrounding Madrid. The city authorities established a regulatory sale price for goods. Authorisation was required to take supplies out of the city.

The city: a great trench. The market stands on the banks of the river, a river that formed a border between one side and the other. Franco’s troops occupied Ferreries, on the right bank of the river, on 18 April 1938, while the Republican Army remained on the left bank. The Ebro river separated the two armies and the city became a war front for a period of nine months. The city’s architectural heritage also suffered the ravages of the war, as revealed by the ruins in Plaça dels Dolors. Although part of Tortosa’s rich artistic wealth had been burned and ransacked at the start of the war, when the city was evacuated, the bulk of the Cathedral Treasury and archives were transported to Barcelona. Nevertheless, the Cathedral Treasury, a collection of 27 pieces of gold and silver, including the 1619 shrine to the Verge de la Cinta (Virgin of the Ribbon) and the 14th-century chalice of Antipope Benedict XIII, would not return to Tortosa once the war was over. It seems that these treasures were taken to France during the retreat and, from there, it was shipped to Mexico to help to support the exiled Republicans.

The bombed bridges. The city had three bridges over the Ebre River: the railway bridge, the Pont de l’Estat and the Pont de la Cinta. The last of these was not rebuilt after the war and its central pillar currently serves as a pedestal for the monument erected by Franco in 1966 in remembrance of the casualties caused by the Battle of the Ebro. The bridges were the main target of the air raids. We can stop for a moment to imagine those moments of horror in the middle of this city, on both sides of the river.

The Italians in Ferreries. We are in Ferreries, the neighbourhood that was home to the militarised industries, such as the Sales foundry, which moved to Vic together with its workers to avoid being destroyed by the air raids. The bell tower of the Neo-Romanesque Church of the Roser was used to position machine guns. When it was reconstructed, it lost 12 metres in height. Franco’s troops occupied the left bank in Tortosa on 13 January 1939.

The return. We will now return to the riverbank and come to Plaça de l’Àngel, one of the city’s key hubs. This was originally the site of the Gothic font that is now located in Palau Oliver de Boteller in Carrer del Doctor Ferran. The residents, who had taken refuge in the mountains until then, returned to the city. Many of them found their homes in ruins and their possessions ransacked. However, not everybody returned. While some stayed away because they had lost everything, for others it was due to repression and exile. In Tortosa, the Mayor Josep Rodríguez, the Councillor and City Judge Francesc Cabanes, the doctor and Councillor Primitiu Sabaté and journalist Sebastià Campos Terré, among others, were condemned to death and shot following a summary court martial.

The reconstruction. We are in Plaça d’Espanya, which is home to the city’s administrative buildings, including the council headquarters, post office and telephone exchange. This square bears witness to the efforts that went into the reconstruction of the city and the style that was used. Tortosa was in a catastrophic condition. Around 3000 of the 4000 city-centre buildings had suffered some degree of destruction. With the exception of the Royal Colleges, which had been used at the start of the Civil War to imprison right-wing citizens waiting to be tried, none of the city’s buildings escaped the ravages of the air raids. The General Directorate for Devastated Regions was created by the new Franco administration to rebuild the towns and infrastructure damaged by the war. The physical task of reconstructing the city continued until the late fifties. However, the trauma experienced by the city’s residents would take much longer to recover from.